When future geologists walk across the Martian surface, they won’t just be exploring alien terrain—they’ll be reading a planetary diary written in stone. Mars preserves a geological record spanning over 4 billion years, and unlike Earth, where plate tectonics constantly recycle the crust and weathering erodes evidence, the Red Planet has kept its ancient history remarkably intact.

The Sedimentary Time Machine

Earth’s geologists have long used stratigraphy—the study of rock layers—to reconstruct our planet’s climatic past. On Mars, this technique becomes even more powerful. The Martian surface is a palimpsest of epochs, with each layer telling stories of ancient rivers, lakes, volcanic eruptions, and dramatic climate shifts.

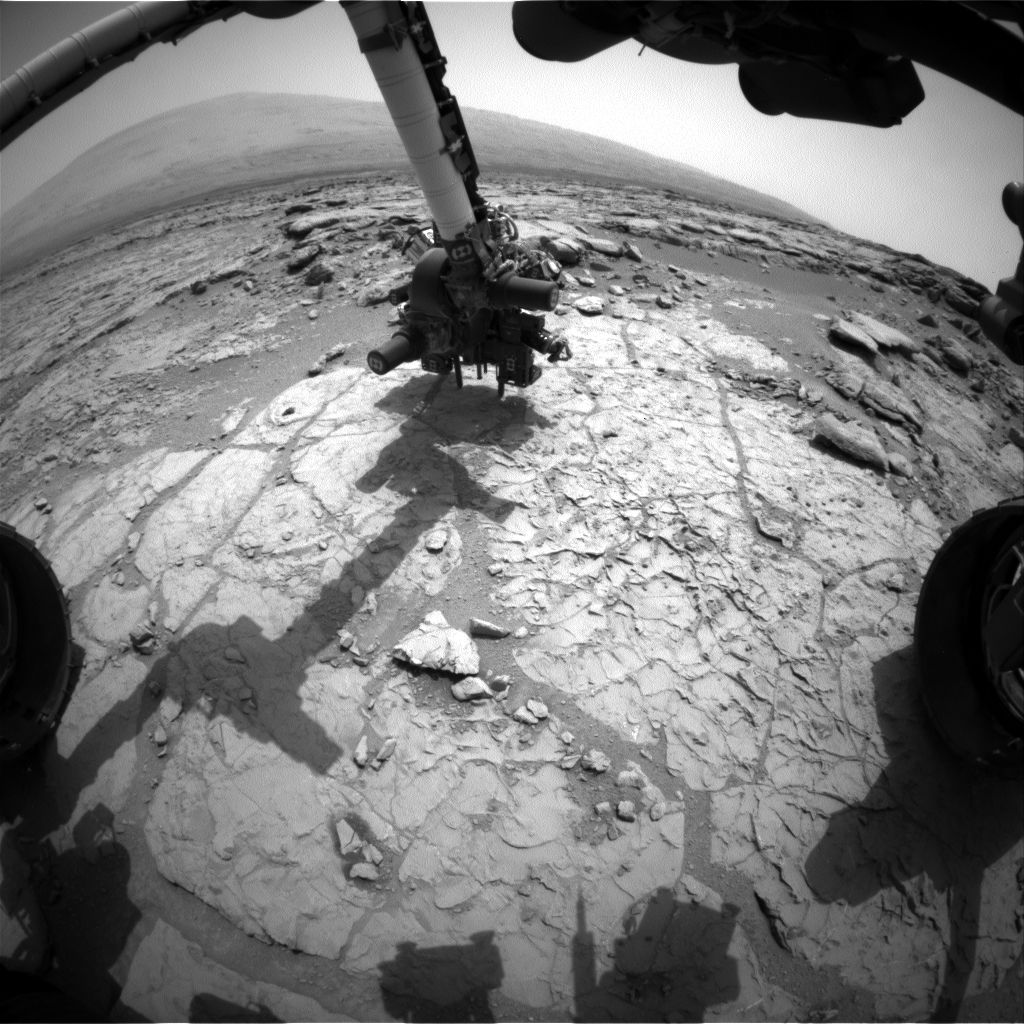

NASA’s Curiosity and Perseverance rovers have already begun this work, drilling into sedimentary formations in Gale Crater and Jezero Crater. What they’ve found is extraordinary: finely layered mudstones that could only have formed in standing water, cross-bedded sandstones indicating ancient river flows, and chemical signatures suggesting alternating wet and dry periods.

What the Rocks Tell Us

The Noachian Period: Mars’ Wet Youth

The oldest rocks, dating from 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago, reveal a dramatically different Mars. Clay minerals like phyllosilicates—which form only in the presence of water with neutral pH—are abundant in these ancient layers. Orbital spectrometers have mapped vast clay deposits across the southern highlands, evidence of a time when liquid water was stable on the surface.

The thickness and extent of these sedimentary deposits suggest not just occasional puddles, but sustained bodies of water. Some formations show layering patterns consistent with lake beds that persisted for millions of years—plenty of time for complex chemistry, and perhaps even the emergence of life.

The Hesperian Transition: A World Drying Out

Around 3.7 to 3.0 billion years ago, Mars began its transformation into the desert world we see today. The rock record from this era shows a shift from clays to sulfate minerals—salts that form in acidic, evaporating water. This chemical transition tells us that Mars was losing its atmosphere and its water was becoming more acidic and scarce.

Yet even during this period, catastrophic flooding events carved massive channels across the surface. These aren’t gentle streams but biblical deluges that moved volumes of water comparable to Earth’s largest rivers. The rocks preserve evidence of these floods in boulder fields, scoured bedrock, and streamlined islands hundreds of kilometers long.

The Amazonian: Deep Freeze with Intermittent Thaws

For the past 3 billion years, Mars has been mostly frozen. But even in this era, the geological record shows occasional liquid water. Recurring slope lineae—dark streaks that appear seasonally—may be produced by briny water flows. Impact craters with ejecta patterns resembling mud splashes suggest subsurface ice melted during impacts. The rock layers continue to accumulate, now primarily from wind-blown dust and occasional volcanic ash, but they still preserve climate information in their chemistry and structure.

Reading Between the Layers: Advanced Techniques

Modern Mars missions employ an arsenal of tools to decode these rocky archives:

Spectroscopy allows rovers to identify minerals from meters away, mapping the chemical fingerprints of past water activity. Different wavelengths reveal different minerals—near-infrared for hydrated minerals, visible light for iron oxides that indicate oxidizing conditions.

Drill cores provide three-dimensional samples through time. By drilling vertically through layers, rovers can sample successive depositional events, creating a timeline of environmental change. The Mars 2020 mission’s sample caching system is collecting these cores for eventual return to Earth, where laboratory analysis can reveal details impossible to detect remotely.

Ground-penetrating radar on orbiters like Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter can see beneath the surface, revealing buried layers and subsurface ice deposits. These instruments have discovered vast ice sheets at mid-latitudes and layered deposits at the poles that record millions of years of dust and ice accumulation—Mars’ equivalent of ice cores.

Isotope analysis of carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen in rocks reveals past temperatures and atmospheric conditions. Different isotopes fractionate (separate) under different conditions, so their ratios act as paleothermometers and atmospheric pressure gauges.

The Polar Archives: Mars’ Ice Core Records

Perhaps the most detailed climate record exists in Mars’ polar ice caps. The north and south poles both contain layered deposits of ice and dust that spiral outward from the pole, creating a visible record of climate cycles.

These layers respond to Mars’ orbital variations—its axial tilt oscillates more wildly than Earth’s (from 15° to 35° over hundreds of thousands of years), dramatically affecting how sunlight is distributed across the planet. During high-obliquity periods, polar regions receive more summer sunlight, causing ice to sublimate and migrate toward the equator. During low-obliquity periods, ice accumulates at the poles.

Ground-penetrating radar has revealed that these polar layered deposits extend kilometers deep, potentially recording climate variations over the past several hundred million years. Future missions may drill these ice deposits, retrieving cores that could reveal atmospheric composition, dust storm frequency, and volcanic activity spanning Mars’ recent geological history.

Implications for Past Habitability

The climate history written in Martian rocks directly informs our search for ancient life. The Noachian clay formations, with their neutral pH and abundant water, represent prime targets for biosignature detection. Perseverance is currently exploring just such a formation in Jezero Crater—an ancient lake bed where organic molecules, if they ever existed, might be preserved in fine-grained sediments.

The transition periods are equally intriguing. Life that emerged during the wet Noachian might have adapted to increasingly harsh conditions, potentially retreating to subsurface refugia as the surface dried out. Modern extremophiles on Earth show us that life can persist in apparently sterile environments—within rocks, in ice, in highly saline or acidic water.

Future Geological Investigations

The next generation of Mars missions will dramatically expand our ability to read these rocky archives:

Sample return missions will bring Martian rocks to Earth laboratories, where instruments too complex for space can perform detailed isotopic analysis, organic molecule detection, and age dating with unprecedented precision.

Human geologists will eventually explore Mars with the flexibility and intuition that rovers lack. A human geologist can examine an outcrop from multiple angles, recognize subtle patterns, and make real-time decisions about where to sample—tasks that take rovers weeks or months.

Subsurface drilling campaigns could access deep aquifers or ancient buried deposits, reaching materials that have been isolated for billions of years. These pristine samples might preserve chemical and biological signatures that surface rocks, exposed to radiation and oxidation, have lost.

Distributed sensor networks deployed across the planet could monitor ongoing geological processes—dust deposition, frost cycles, slope failures—adding a temporal dimension to our understanding of how Martian climate operates today, which helps us interpret the past.

A Planetary Rosetta Stone

Mars offers something precious that Earth cannot: a nearly complete geological record of planetary evolution. Where Earth’s plate tectonics have erased most traces of our first billion years, Mars has preserved its childhood. Where Earth’s abundant water and life have transformed surface rocks beyond recognition, Mars has kept its original signatures intact.

Every rock layer is a chapter in a 4-billion-year story of planetary climate, from a warm, wet world to a frozen desert. As we learn to read this archive with increasing sophistication, we’re not just learning about Mars—we’re learning about the range of possible planetary climates, the factors that make worlds habitable, and the ways planets can lose their habitability.

This knowledge is essential for understanding our own planet’s past and future. It informs our search for life beyond our solar system—teaching us what biosignatures to look for and what planetary conditions might preserve them. And it prepares future Martian colonists to understand the world they’ll call home, from where to find buried ice to which rocks might contain valuable minerals.

The Martian rocks are waiting. Each layer holds secrets, and we’ve only begun to read the first pages of this epic geological chronicle. As our missions become more sophisticated and eventually bring samples home, the story will become clearer—a story written in stone, preserved for eons, waiting for curious minds to decode its messages about climate, water, and the possibility of life on the Red Planet.