The Politics of Space Governance: Who Owns Mars?

Examining treaties, emerging policies, and the challenges of international cooperation in planetary colonization

With humanity standing on the precipice of interplanetary expansion, a fundamental question looms: who gets to own Mars? The Red Planet, once the domain of science fiction, has become the focal point of a very real geopolitical and legal struggle. With government space agencies and private companies racing to establish a human presence on Mars within the next decade, the international community faces unprecedented challenges in creating governance frameworks for a world 140 million miles from Earth.

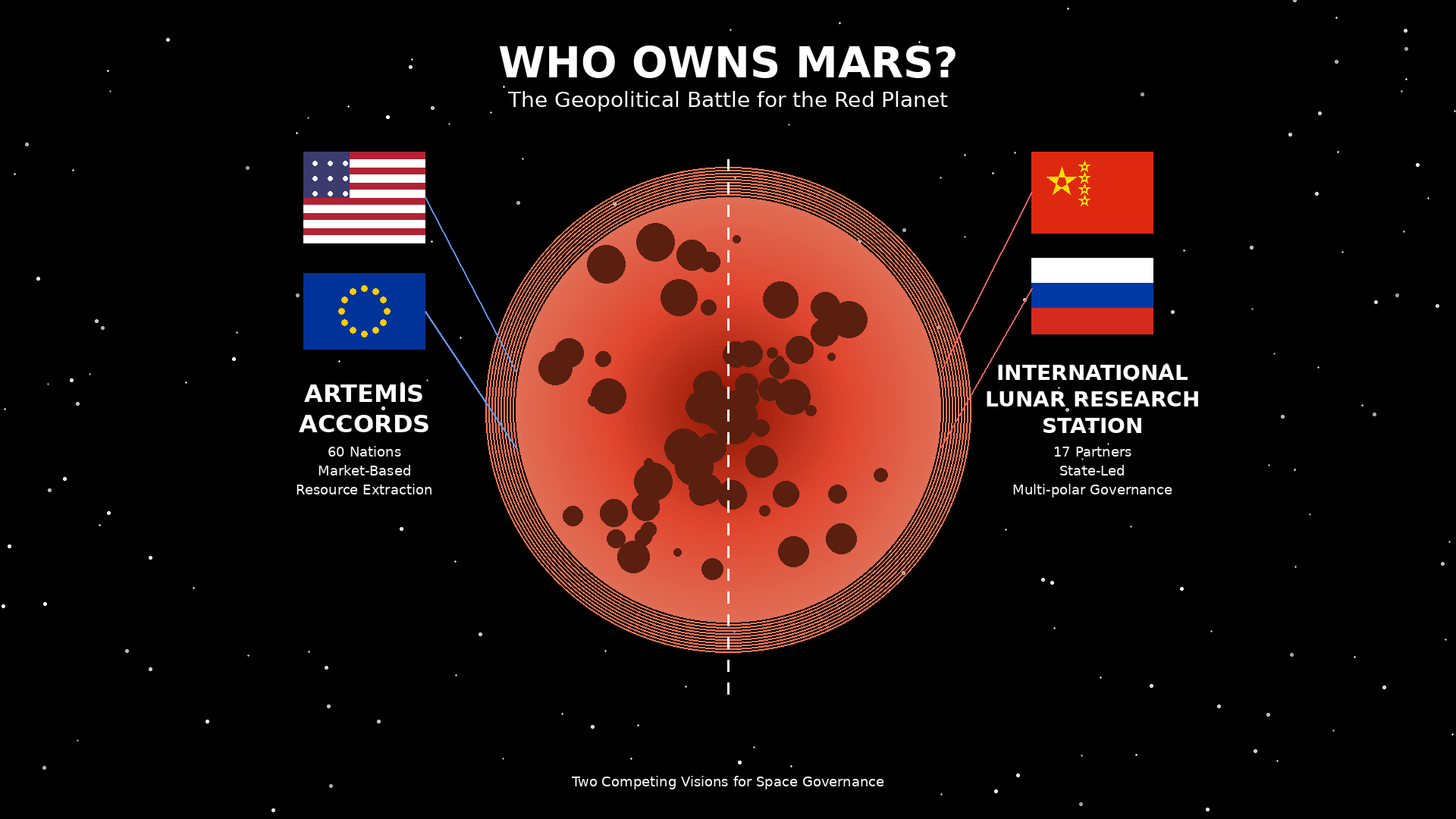

Recent developments have transformed this debate from theoretical exercise to urgent policy priority. In December 2025, President Trump issued an executive order on Ensuring American Space Superiority, directing NASA to establish permanent lunar outpost elements by 2030 as stepping stones to Mars exploration. Meanwhile, as of early 2026, 60 countries have signed the Artemis Accords, a U.S.-led framework that explicitly permits space resource extraction—a position that China and Russia vehemently reject as they build their rival International Lunar Research Station (ILRS).

The Foundation: Cold War Treaties in a New Space Age

At the heart of space governance lies the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST), negotiated during the Cold War when only the United States and Soviet Union had launched satellites. The treaty, now ratified by 115 countries, established foundational principles: outer space is the province of all mankind, celestial bodies cannot be appropriated by any nation, and countries bear responsibility for both governmental and private space activities conducted under their jurisdiction.

Article II of the OST declares that outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty. This seemed straightforward in 1967. But today, as nations and corporations plan to extract water, minerals, and rare earth elements from Mars, a critical ambiguity has emerged: does the ban on appropriating territory also prohibit appropriating resources extracted from that territory?

The 1979 Moon Agreement attempted to clarify this, declaring lunar resources the common heritage of mankind and requiring an international regime to govern their exploitation. But the treaty was dead on arrival. Only 18 countries ratified it, notably excluding the United States, Russia, China, and every other major spacefaring nation. As one legal scholar observed, the Moon Agreement was seen as creating a moratorium on resource extraction until an international regime could be established, effectively killing commercial incentives before they could develop.

The Artemis Accords: A New Framework or American Hegemony?

Into this legal vacuum stepped the Artemis Accords. Announced in October 2020 by NASA and the U.S. State Department, the Accords represent the first major international space agreement since 1979. The document builds on OST principles while establishing practical guidelines for lunar and Martian operations, including transparency, interoperability, emergency assistance, and, most controversially, space resource utilization.

Section 10 of the Accords affirms that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty. This codifies the U.S. position, first enshrined in the 2015 Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, that while no nation can claim sovereignty over Mars, entities can own the resources they extract, analogous to fishing rights on the high seas.

The Accords have gained substantial traction. By November 2025, 60 countries had signed on, including most U.S. allies and major spacefaring nations like Japan, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Australia, and South Korea. The Philippines became the 59th signatory in October 2025. Notably, Luxembourg, the UAE, and Japan—countries that have passed domestic space mining laws, are all signatories.

But the Accords have sparked fierce criticism. Russia and China have refused to sign, arguing they undermine multilateral governance by bypassing United Nations oversight. Chinese state media has characterized the initiative as a colonial-era enclosure movement, accusing the U.S. of pursuing colonization and claiming sovereignty over the moon under the pretext of cooperation. Russia’s space agency chief has described the Accords as attempting to expropriate outer space.

The introduction of safety zones under the Accords has proven particularly contentious. While presented as necessary to prevent collisions and harmful interference between operations, critics argue these zones could function as de facto territorial claims, fundamentally testing the OST’s prohibition on appropriation. As one legal analysis notes, the distinction between private property rights and sovereign territory becomes increasingly difficult to maintain when operators establish exclusive zones around resource-rich sites.

The Private Sector Wild Card

Perhaps the most profound shift in space governance involves the role of private companies. SpaceX, Blue Origin, and other commercial entities are no longer supporting actors, they are driving the entire enterprise. SpaceX’s Starship is central to NASA’s Artemis program, while Blue Origin, Dynetics, and Lockheed Martin have secured major contracts for lunar infrastructure.

The Artemis Accords explicitly encourage private sector participation, affirming that commercial entities can engage in space mining and resource utilization. NASA has already signed contracts with four private companies to collect lunar resources, establishing a precedent for commercial extraction. Since 2000, commercial space companies have received over $7 billion in government support. In 2020 alone, NASA awarded nearly $1 billion for lunar lander development and another $370 million in tipping point contracts for near-commercialization technologies.

However, this creates significant governance gaps. Under Article VI of the OST, states bear international responsibility for national activities in space, whether carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities. But as scholars note, the Accords may shed private corporations of direct accountability, creating scenarios where rogue entities could violate international agreements without facing severe consequences.

The legal framework for regulating these activities remains underdeveloped. Who has authority to license and oversee commercial Mars missions? The 2015 U.S. Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act authorizes resource extraction but doesn’t specify which agency regulates these operations. Various legislative proposals for mission authorization or on-orbit authority remain pending, leaving significant regulatory uncertainty.

National Space Mining Laws: The Race to Regulate

Unable to wait for international consensus, several nations have unilaterally passed domestic space mining legislation. These laws provide crucial insights into what a future international framework might contain.

The United States led the charge with the 2015 Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, which explicitly grants U.S. citizens rights to extract and sell space resources while clarifying that this doesn’t constitute sovereignty claims over celestial bodies.

Luxembourg followed in 2017 with comprehensive space resources legislation, positioning itself as Europe’s hub for space mining ventures. The law recognizes that space resources are capable of being owned and requires Ministry of Economy authorization for all extraction activities. Luxembourg has aggressively courted space mining companies, offering favorable regulatory conditions and investment incentives.

The United Arab Emirates enacted Federal Law No. 12 in 2019, establishing a licensing system through the UAE Space Agency for all space resource activities, from prospecting to extraction. The law emerged as the UAE expanded its space ambitions with Mars probes and lunar rovers.

Japan became the fourth nation in 2021 with its Act on the Promotion of Business Activities Related to the Exploration and Development of Space Resources. Article 5 explicitly confers ownership of mined materials to the extractor, subject to an approved business activity plan.

In 2024, the U.S. and Luxembourg strengthened their partnership with an agreement to enhance cooperation on space resource projects. Meanwhile, a 2025 study found that space resource legislation has had measurable impacts on attracting investment to these countries’ space sectors, providing empirical support for the business case behind these laws.

The China-Russia Counter-Coalition

While the U.S. builds its Artemis coalition, China and Russia have forged their own lunar and Mars partnership through the International Lunar Research Station. Announced in June 2021 after several years of bilateral cooperation, the ILRS represents China’s first major leadership role in international space cooperation and Russia’s pivot away from Western partnerships.

The ILRS roadmap envisions three phases. Phase one, extending through 2025, involves reconnaissance and technology verification through missions like China’s Chang’e-4, 6, and 7 and Russia’s Luna 25, 26, and 27. Phase two (2026-2035) focuses on construction, including massive cargo delivery and the establishment of in-orbit and surface infrastructure for energy, communications, and resource utilization. Phase three looks toward sustained human presence beyond 2035.

As of April 2025, 17 countries and organizations had signed onto the ILRS vision. In March 2024, Russia and China announced plans for an automated nuclear power plant to be built on the Moon between 2033 and 2035 to power ILRS operations, a project that leverages Russia’s nuclear expertise with China’s expanding space budget, which reached $14.15 billion in 2023, a 19% increase over 2022.

The geopolitical implications are stark. Both China and Russia have explicitly characterized their partnership as a counter to American dominance in space. They advocate for what they term shared multi-polar governance, rejecting the U.S. vision of space as a global commons underwritten by American power and commercial providers. Through the ILRS, they are incrementally establishing alternative norms that diverge from U.S. proposals.

This competition extends to establishing technical standards. NASA is developing LunaNet, an open, interoperable lunar communications and navigation framework. If American systems are established first, they become the default. But China launched Queqiao-2 in 2024 to provide relay services for far-side operations and is developing concepts for a 30+ satellite lunar communications constellation that could establish an alternative system through the 2030s and 2040s.

The Stakes: Why First Matters

The race to Mars is fundamentally about establishing norms, standards, and precedents that will govern human activity beyond Earth for generations. As one policy analysis notes, precedent is powerful: the group that arrives first at priority sites can set its practices as the de facto standard.

Several tangible stakes are in play:

- Control of communications and navigation standards: Will Mars missions use American LunaNet protocols or Chinese alternatives?

- Early presence on scarce, resource-rich sites: The Martian south pole contains water ice essential for fuel production and life support. First movers can establish operations at the most valuable locations.

- Reputation and alliance structures: Success strengthens existing partnerships and attracts new participants. NASA’s Artemis program has already driven dozens of bilateral agreements.

- Momentum in the emerging space economy: Early commercial success in resource extraction and in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) creates competitive advantages. NASA has contracts with private companies specifically to establish this momentum.

Congress has explicitly linked American leadership in space to global prestige and alliance cohesion. The concern is not merely symbolic. If China lands astronauts on Mars first, the ILRS narrative gains momentum, and alternative governance frameworks become more credible.

Governance Gaps and Future Challenges

The current state of space governance reveals profound inadequacies. While there is broad consensus on the need for new frameworks, with the U.S., Russia, China, and EU all calling for enhanced regulation, there is currently no viable pathway to codify even widely accepted norms into binding international law.

Several critical issues remain unresolved:

- Property rights vs. sovereignty: Can the distinction between owning resources and claiming territory truly hold when operators establish permanent installations and exclusive safety zones?

- Regulatory authority gaps: Who licenses Martian mining operations? Who enforces safety standards? Who resolves disputes between operators from different nations?

- Liability regimes: Under the OST, launching states bear liability for damage caused by their space objects. But how does this apply to permanent Martian settlements? What about accidents involving private operators?

- Environmental protection: Should Mars be subject to planetary protection protocols? How do we balance resource exploitation with preserving the planet for scientific study?

- Equity and access: Will space resources benefit all of humanity, or only technologically advanced nations and wealthy corporations? The Moon Agreement’s ‘common heritage’ principle failed, but the current trajectory toward unregulated extraction troubles many scholars.

Scholars have proposed various solutions, including a Conference of the Parties (COP) model similar to climate agreements. In December 2025, a major policy paper from Harvard’s Belfer Center advocated for an OST-COP that would provide a forum for ongoing treaty interpretation and development of best practices. The European Union has proposed its own Space Act, with the legislative proposal delayed to 2025 but expected to address space traffic management, critical infrastructure safety, and environmental concerns.

The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UN COPUOS) continues multilateral discussions, and UNOOSA held a major Conference on Space Law and Policy in November 2025. But these efforts have yet to produce binding legal frameworks that can keep pace with technological and commercial developments.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The question of who owns Mars is not merely academic, it will shape the future of human civilization beyond Earth. The current trajectory suggests a bifurcated space order: an Artemis coalition of 60 nations embracing market-friendly resource extraction and public-private partnerships, facing off against a China-Russia ILRS alliance advocating for state-led, multipolar governance.

This division poses risks. Without agreed-upon rules, disputes over resource-rich sites could escalate. Competing technical standards could fragment Martian infrastructure. The absence of clear property rights could chill investment, while unregulated extraction could trigger accusations of colonial exploitation.

Yet opportunities remain. The Artemis Accords, despite their flaws, represent meaningful progress, translating abstract treaty principles into concrete operational guidelines and establishing that resource extraction can occur without sovereignty claims. The proliferation of national space mining laws creates a body of practice that could inform future international agreements. And the sheer number of stakeholders,government agencies, private companies, international organizations creates pressure for coordination.

The next decade will be decisive. Artemis 3 is scheduled for no earlier than mid-2027, while China targets 2030 for its first crewed lunar landing as a precursor to Mars. The nation or coalition that establishes sustained presence first will wield enormous influence over the norms and institutions that govern Martian settlement.

As NASA Administrator Bill Nelson stated when discussing the Artemis Accords, space exploration has always combined scientific discovery with geopolitical positioning. The politics of Mars governance will determine not just who profits from Martian resources, but what values and systems, democratic or authoritarian, open or closed, multilateral or unilateral, define humanity’s presence on a new world.

The Red Planet beckons. The laws we write now will echo across the solar system for centuries to come.